Maqedonishtja e lasht bija e shqipes dhe toponimet "CA"

Sun, 07 Dec 2025

Ndiqni historitë e akademikëve dhe ekspeditat e tyre kërkimore

Chamëria: The Land Where Only Albanian Was Spoken and Sung

There is a profound and overwhelming feeling of distress and sorrow when you stand in Chamëria, in those settlements where everything Albanian or 'Albanian' is banned and punished.

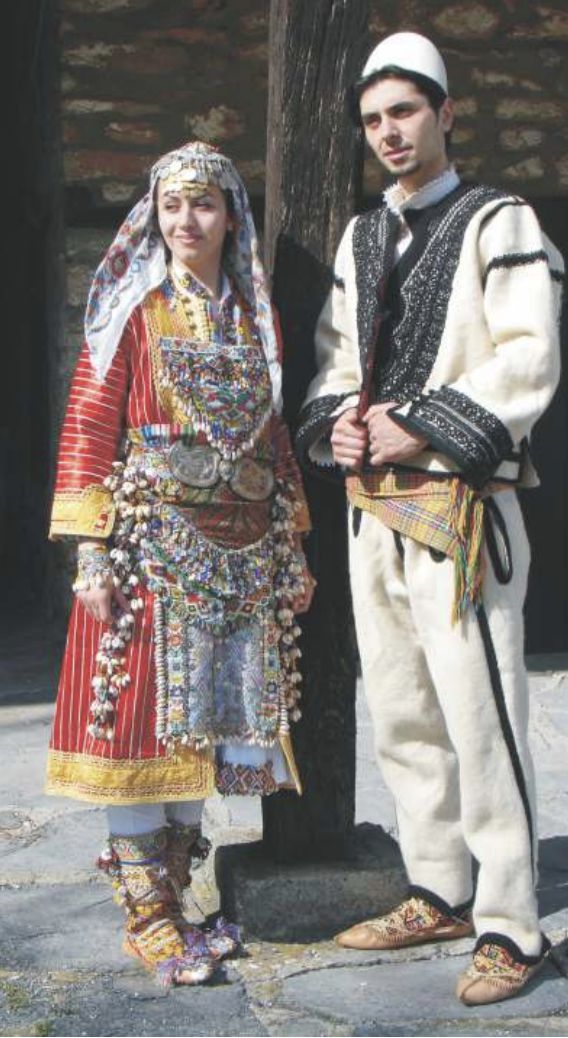

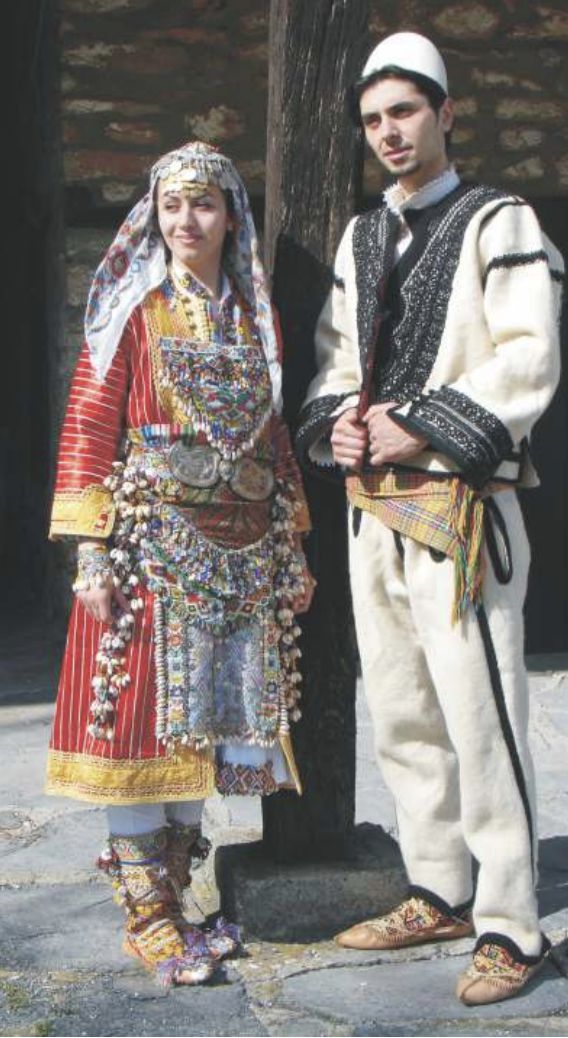

The journey through this region, once occupied by the Greeks and their Hellenizing forces, has deeply buried the Albanian element, or what is now falsely called the Arvanites in this area. This was once a land of a hardworking people, living in fertile lands with a rich historical and cultural heritage, a land that was filled with the treasure of Albanian traditions: its clothing, dances, customs, and diverse folk practices.

During my visit to the villages of Chamëria, I was struck by the fact that the main towns surrounding the border, and even deeper into northwestern Greece, are surrounded by villages with distinctly Albanian names.

It is said that in the homes of the elderly, they still speak Albanian, and as a visitor, you’re left in awe when you hear it. It feels as though you’ve suddenly found yourself in the southern regions of Albania.

These are the cities that were once Albanian: Gumenica, surrounded by Albanian villages such as Dushku, Grikohori, Salicaj, and Paramithia with Globoçari, Skupica, Sharati. Margëlliçi is encircled by Luarati, Karbunari, and Margariti, while Filati is bordered by Shqetaqri, Spatari, and Çifligu. And then there’s Janina, with its ancient tomb of Ali Pasha Tepelena, and Preveza, along with Arta, where the 13th-century fortress stands, built in the Illyrian-Dardanian style, with an ancient bridge over a river, just like those in Albania, in Shkodër or Gjakovë.

When you visit any of these villages in northwestern Greece, as dusk falls and the men gather in the local cafés, you hear that many of the elderly speak only Arvanitika-Albanian among themselves, a dialect that is uniquely Albanian, characteristic of this area. It is a form of Albanian that remains "half-kept," neither fully preserved nor cultivated by the generous and noble people who still hold on to it.

However, due to the forced departure of Albanians and their mandatory assimilation, especially during the ultranationalist Greek politics of the 20th century, and the communist regime in Albania, it has become increasingly rare to find "Albanians" in these areas, no matter how much you try to converse with them in their native tongue.

Sadly, even those few who remain now fear speaking Albanian and identifying as Albanians. This comes from the heavy repression and hidden persecution they endured, which reminds you of the time of persecution in Albania.

In every village in this region, there are few, if any, Albanians, especially those of the Muslim faith, the Chams. Even the Orthodox Albanians, the residents of this area who once owned the land and properties but never received official deeds, refuse to speak Albanian in any circumstance.

In fact, when you approach one of them and speak Albanian, they retreat in fear, just like during the Communist regime in Albania, when Chams feared revealing they were from Chamëria.

I met a woman from southern Albania who worked for a family in one of these villages (I won’t disclose her name or the village, as she feared the "danger" it could bring). She told me that while cleaning the house, she found on a wooden plank the carved names of an Albanian Muslim couple, Chams.

According to experts on Cham issues, the Arvanites, both Orthodox and Muslim (Chams), are considered a people of shared origin, the ancient Pelasgians, who are the ancestors of modern-day Albanians. They speak the language and uphold the culture of the Arvanites, Albanians, but the existence of this forgotten people and their neglected heritage is a result of both the half-century-long rule of Enver Hoxha and the negligible attention paid to them over the last 23 years, since the fall of his regime.

It wasn’t until a “Treaty of Friendship” between Albania and Greece, signed by President Berisha, that this issue was even mentioned, after 50 years of silence.

The assimilation and "forgetfulness" of this population is believed to have been fueled by the fear of losing the support of the Greek state and its cultural policies for minorities, despite the fact that the Arvanites consider themselves indigenous to Greece. This is a question that leaves much to discuss and one that today’s Albanian politics has yet to address, especially in light of international conventions and laws.

While there is no official study or in-depth research, there are writings and reports by Edith Durham, along with works by Albanian scholars, historians, and journalists over recent decades, as well as documentaries on Chamëria, shedding light on how many Albanians still remain in these regions, and how Albanian these regions still are.

One Albanian who emigrated to Gumenica in 1990, after the fall of Communism in Albania, anonymously shared that: *“When I left Albania and settled in Gumenica, I stayed at a two-story house typical of this city, which resembles Saranda. I slept on the second floor, while the first floor was a shop that collected milk from the surrounding villages for the market.

The next morning, after I had crossed the border, I started to wonder if I had truly crossed it, because every morning, they spoke to each other in Albanian as they went about their business.

What surprised me, though, was that as of today, I don’t know what happened to these villagers or what became of them. After 1993, when more Albanians came from Albania, none of these villagers spoke Albanian anymore when they brought in the milk and produce.”*

And this, he explained with regret, was the consequence of the policy pursued by the Greek state — a policy that has remained unchanged and constant, driving Albanians toward assimilation and pushing them away from the lands that were once purely Albanian.

Hope this version captures the depth of emotion and poignancy of the original, with an added sense of outrage and sorrow at the fate of the Cham people.

Sun, 07 Dec 2025

Fri, 18 Jul 2025

Lini një koment